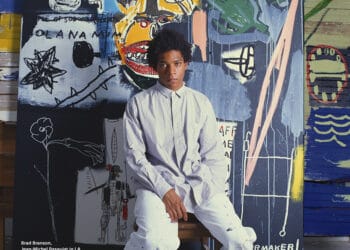

Ed Moses is a remarkable figure in contemporary art who keeps getting better and better. His recent show “Ed Moses: Now and Then” closed August 29 at the William Turner Gallery at Bergamot Station in Santa Monica, California, and included new works from 2015 which had never been seen by the public before.

Although I attempted to record our interview on my iPhone, the recording inextricably stopped several seconds after it started. Mindful of the art groupies, friends, patrons and others who were waiting to get a piece of Ed’s attention, I stopped trying to erase videos and manage my storage settings and decided to keep talking, and do my best later on to remember what we’d said to each other.

“I like your shoes.”

That was the first thing Ed said to me, as crowds were filtering in, getting cocktails or organic hot dogs from the patio. The rest of the conversation, though I recall with some accuracy what was said, I could not place in chronological order.

“Hot pink shoes for a hot day,” added his friend, an art consultant who lives in Beijing and Los Angeles. I’d gotten dressed for a workout and didn’t have time to change into something more upscale, but no one was dressed to impress; rather for comfort and freedom. “I know it’s too hot for long sleeves,” said one man, dressed a bit like Marcel Marceau in black pants and a black and white horizontally striped cotton top, “but we rode bicycles.” Another woman introduced herself to me as “the world’s most prolific collector of dog art.” My sweatpants and hot pink Nikes? No problem.

Although the atmosphere was decidedly laid back, there was an implicit understanding everyone pretended not to think about that something serious was nonetheless happening. After all, these paintings sell for upwards of $60,000. Ed Moses is considered by more than a few people the best and/or most important painter living in Los Angeles today. He is, however, far from pompous. “Yes, sit down,” he invited me, “and I’ll tell you all the lies you want.”

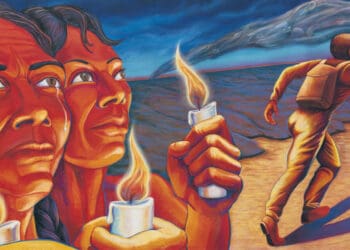

“Your recent work has gotten less pretty,” I postulated, “And more brutal, so it’s more compelling.”

“I like that,” he said.

We talked about the backs of the paintings. I said they tell a story a hundred years from now when the painting has traveled to various museums or through a chain of ownership, and he agreed that they can reveal more than the front of a painting. To a person who loves painting with a passion the back of a painting represents the “inner life” of the painting; it could be the fetishistic attachment of the artist to that which is not on display or for exhibit turned outward in a display of introspection, defiance, or vulnerability; it could be what separates the mere art aficionado from the fanatic, just as a weekend tourist in Napa Valley might conspicuously smell and swill the wine in the glass, but a sommelier will know how far to fill the glass, when to decant, and when the bouquet is open. “You can say I said whatever you want.” he told me, when I told him I was going to have to rely on a mental recording of the conversation. But the things he actually said were delightful.

He talked about Kauffman and Reinhardt; Paris in 1958; UCLA; and (if I understood correctly) an image of a woman or cat exhaling flames. He talked about soaking his canvases with water before applying brushstrokes and using ground glass. He talked about the white with black piping patent leather wedge sandals of a woman in the crowd, and the reflections of the paintings on the high gloss gallery floor.

A way of seeing tantamount to a way of being: the antithesis of what Reinhardt would call the disreputable practices of artists-as-artists. He complimented an observation that the paintings were about painting rather than meaning after the phrase no meaning came out of his mouth and I’d chimed in, excitedly. He had just finished telling me that there were no mutations in his paintings, but futations, and I’d asked what a futation was. “It doesn’t mean anything.” “It has no meaning.”

Fire? No. Pounding nails? Yes.

“You can make it about whatever you want. Whatever it is to you, it’s right,” he said.

I see two closely related themes in Moses’ work; the (concrete, absolute, sui generis yet organic) brushstroke, and the (abstract, man-made, egoic and ephemeral) cycle of creation and destruction. There were references to Japanese screens and printmaking and its historical influence in 20th century; European painting; patterns of lace; assemblage and deconstructivism; slick use of color and quasi-Scientific symbols of protons. There were dual impulses to allow and shape the flow of paint and a merging of liquidity and time.

Ed Moses was born in 1926 and will be 90 years old next April. I feel very privileged to have had the opportunity to meet and speak with Ed in person along with seeing the new work, and would like to express my special thanks to Ed for his generous kindness, as well as William Turner for hosting the exhibit and Stephen Volenec for his encouragement to do the interview.

This story is copyright 2015, The Hollywood Sentinel, all world rights reserved. The offices of The Hollywood Sentinel do not endorse any advertising or links that may be found on or in connection with this story.

Moira Cue art and literature editor of The Hollywood Sentinel and President of Moira Cue Multimedia. A fine artist, writer, actor, and singer, Moira Cue has appeared on stage at the Viper Room, Key Club, and The Mint among more. Contact Moira at www.TheHollywoodSentinel.com.