By Moira Cue

Edith Wharton’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Age of Innocence, details life among the upper class of New York Society during the late 19th century. Like many Pulitzer Prize winning novels, this story, too, became a Hollywood movie, most recently in 1993, seventy-two years after the original story won the Pulitzer in 1921.

The first film adaptation was a silent film released by Warner Brothers in 1924. The second version was released in 1934 by RKO Studios.

The third adaptation was directed by Martin Scorsese and starred Daniel Day-Lewis as the novel’s protagonist, Newland Archer, and Michelle Pfeiffer and Winona Ryder as his competing love interests, the Countess Olenska and May Welland, respectively.

The novel succeeds in capturing perennial attention because Wharton (born in 1862) wrote so precisely about what she knew, the high society New York she witnessed as a child. Even among Pulitzer Prize winners, Wharton’s gift is remarkable.

Her ability to render the psychic arcana of a small clique of wealthy families is almost overshadowed by the encyclopedic density of allusions and references to artistic, cultural, and historical minutiae specific to Old New York Society circa 1875 which literally require footnotes. If you read Wharton’s footnotes thoroughly, you will learn about down to its buttonholes (which Newland Archer adorned with a single flower, preferably a gardenia). You will also learn about Europe at the time, to a lesser extent.

For one who is more accustomed to reading contemporary fiction, the humanity of Wharton’s characters really doesn’t compel or shine through until the reader’s mind has adjusted to the ramifications of (literary) time travel, as well as the culture shock of glimpsing behind the veil of an elite social strata where money and position is something you inherit rather than something you earn.

But rest assured, if you are patient, you will not only adjust to but enjoy the stylization, and before you realize, the story will sink its hook in. This is a Symbolist story, which, to oversimplify, represents the relationship of New York to Europe as America approaches the turn of the 19th century. The story begins as Countess Olenska, born in New York, having been seduced by a European rake and the tolerance of his set for infidelity, has returned to her own kind, where she longs for a certain purity. Ultimately, having been “contaminated” by European aristocratic decay, it is only in renouncing a future in New York that she becomes an unlikely guardian of its ideal—an ideal which progress disintegrates within a generation.

Newland Archer is engaged to May Welland but falls desperately infatuated with the Countess. He is smitten by her inappropriate behavior and disregard for social norms because she is natural in her emotions, and surrounded by “interesting” artists and literary types. He wants to break off the engagement and even after he is married, his tortured longing continues.

The addictive elements of the plot structure are delayed gratification and suspense, which can almost feel formulaic. Ironically, the realism of Newland Archer is most evident and moving at the end of the novel. The book’s final scene takes place in Europe when Newland is older and wiser, closer to the “contemporary time” of publication of the novel. In this scene, Newland’s hollowness is revealed, movingly, as his most contemporary psychic characteristic, made poignant by the reverberation of all the “stuff” around him: the serving platters, the customs, the parties, the mannerisms. Newland Archer’s emptiness, born of a life constructed by exterior social forces, is transformed by noble restraint into a shrine of the memory of dualistic love: the love that never was to be, and the love his world made room for.

10 More Things about Wharton

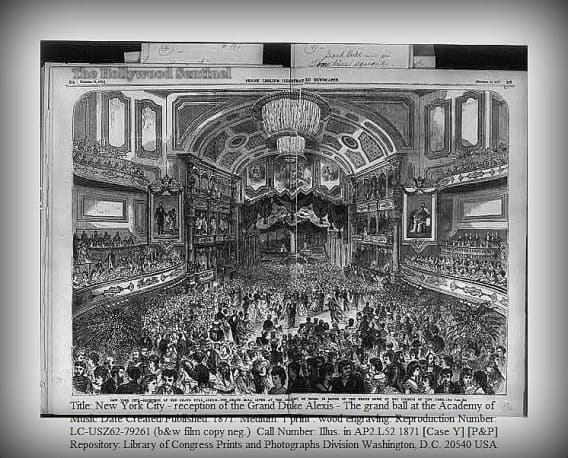

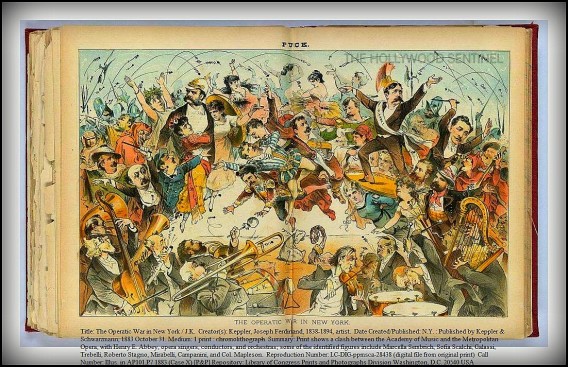

- The battle between The Academy of Music and The Metropolitan Opera House

The Metropolitan Opera House was organized by Mrs. William K. Vanderbilt in 1883 as a competitor to the established Academy of Music in New York when despite her husband’s tremendous wealth, she was unable to procure a box at the Academy of Music. The Vanderbilts were considered at that time “interlopers” by Old New York, much like the characters the Beauforts, who are extremely wealthy, but considered “vulgar” by the old monied families accustomed to running elite society. The latter venue is where the opening scene of The Age of Innocence takes place, with the explanation: “Though there was already talk of the erection, in remote metropolitan distances “above the Forties,” of a new Opera House which should compete in costliness and in splendor with those of the great European capitals, the world of fashion was still content to reassemble every winter in the shabby red and gold boxes of the sociable old Academy.”

- “Pardon my Latin”

Archer Newland, whose family stood as a pillar of Old New York, was so well-bred that when astounded or exasperated, he the uttered Latin phrase “Santa Simplicitas!” (or, “Holy Simplicity”) rather than cuss. Sounds a little more elegant than “freakin.”

- Cult Phenomenon

Edith Wharton, like a few other beloved Pulitzer winners such as Ernest Hemmingway or Margaret Mitchell, is a cult phenomenon, even today. Ms. Wharton’s estate (The Mount) made headlines in The New York Times in September of 2015 when the Edith Wharton House Museum, her former home in Lennox, Massachusetts, cleared its debt of $8.5 million. There is also an international membership organization dedicated to Wharton scholarship, the Edith Wharton Society, by Professor Annette Zilversmit in 1983. Her former home can be toured after its winter closure beginning again in May of 2016.

- Beyond Literature

Wharton’s impact goes far beyond literary circles. She is considered one of the mothers of the field of interior design, who understood proportion and balance far better than many of the fashionable designers of The Gilded Age. Her first book, the non-fiction The Decoration of Houses, co-authored with Ogden Codman, Jr., is considered influential and relevant today.

- First Woman

Wharton was the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize, first to receive an honorary doctorate from Yale University, and first woman to obtain full membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters. To be fair to the Pulitzers, Wharton’s was only the third award given, and in the Pulitzer’s first ten years, 40% of the novel awards went to female authors. During the last ten awards given, the Pulitzers for fiction have achieved gender parity at 50%.

- 100 Years of Change

The dawn of the 20th century was an exciting time where technological advances changed forever the way society functioned, much as the dawn of the 21st century has brought new advances in genetic sciences, the Internet, and mobile communication. It is only, for example, looking back from a vantage point where no matter where you are, your family can call and check in on you, that being “out” and using a pay phone or answering machine and then waiting rather than sending a text message seems “innocent.” In fact we have no excuse to ignore each other anymore other than “my cell phone battery died,” and even those of us who grew up without cell phones marvel with some envy the luxury of being gone and not being able to be digitally tracked.

The British ship Mauretania, which won the blue ribbon for speed in 1906, was the first to cross the Atlantic in less than five days; the first tunnel under the Hudson was opened 1904-5; the first powered airplane flight took place in 1903; electric lightning was established in New York when the Edison Illuminating Company opened its Pearl Street power station in 1882; Marconi patented the first system of radio telegraphy (without wires) in 1896. The book’s protagonist is only dimly aware of people who believed such advances were on their way, but has very little interest in such things.

The “age of innocence” also refers to this period of time after the Civil War and before the Great War (WWI).

- Edith Wharton, like the heroine in The Age of Innocence, left the Old New York of her youth and spent her last twenty five years as an expatriate in Paris.

- Edith Wharton only began to write fiction seriously after a nervous breakdown in 1898, which marked the end, in the author’s words, “of trying to adjust herself to her marriage.”

- What Others Have Said

“The note of distinction is as natural to Edith Wharton as it is rare in our present day literature … She belongs to an earlier age, before a strident generation had come to deny the excellence of standards.” -Vernon L. Parrington, Jr., Pulitzer Prize winning historian, 1871-1929

- Legion of Honor

Ms. Wharton was awarded the French Legion of Honor, the highest civil award the French government gives to foreigners, for her volunteer work during World War I.

This content is ©2016, The Hollywood Sentinel, Moira Cue, all world rights reserved.