By Moira Cue

Agnes Martin was an iconic American painter, who lived from 1912 to 2004. On view through September 11, 2016, is her first posthumous retrospective in the United States, at the Broad Contemporary Art Museum at LACMA; on the third floor.

This is a must-see for anyone in, or traveling to, Los Angeles. Reading about Agnes’s work is insufficient; no matter how well described or photographed, the work really cannot be reduced to words or captured by photography.

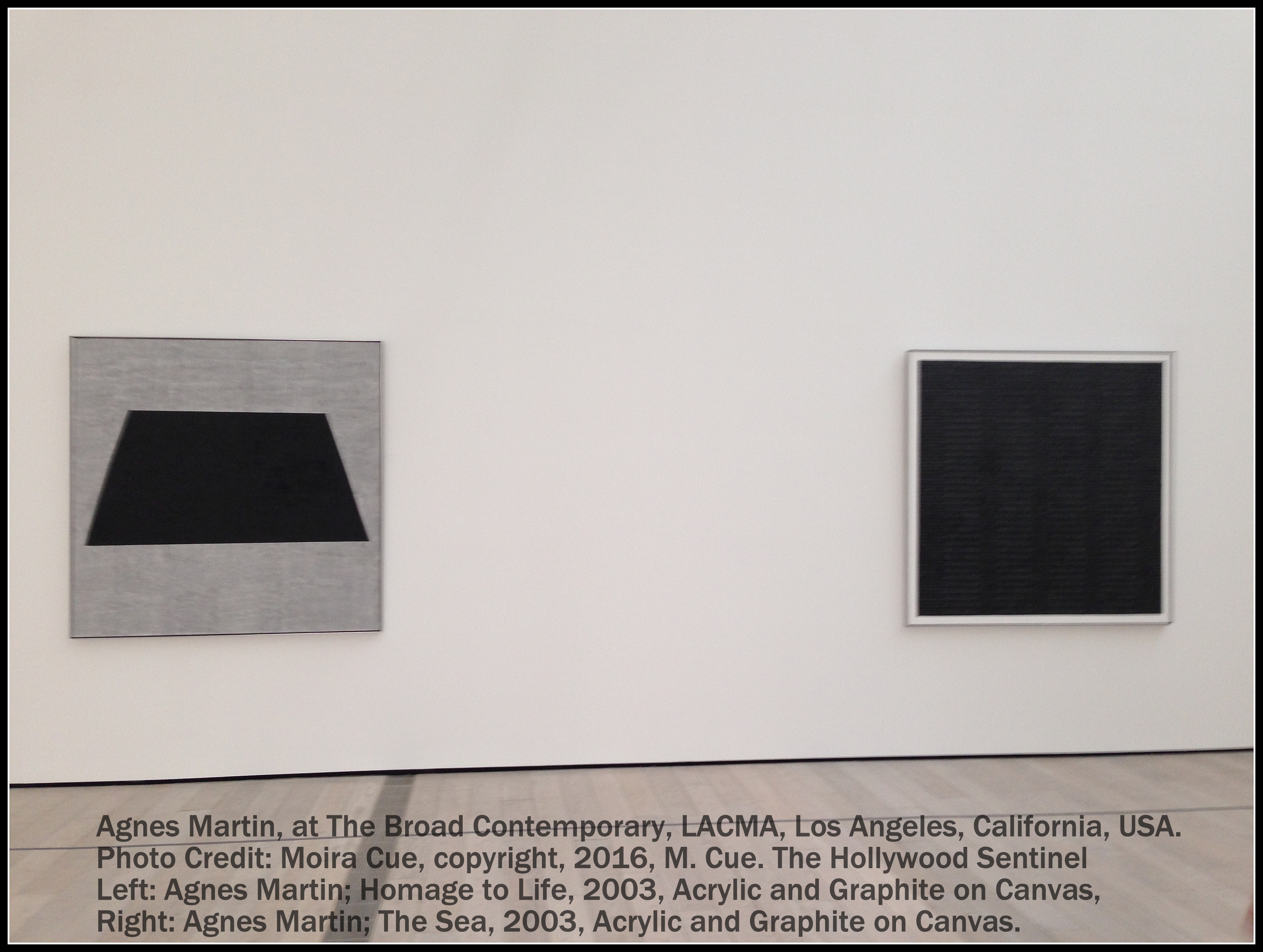

Martin is known for her trademark use of graphite and her exploration of the “grid.” Her works can be viewed through the lens of minimalism, but they paradoxically connect to the viewer’s emotional receptivity through expressionism―from a distance of ten to twenty feet, the work is geometric, cold, and monumental. But the same work, from an intimate distance of three-eighteen inches (and you will be leaning in, nose forward, with your toes behind a grey line taped to the floor), is delicate, self-questioning, and vulnerable. Those tiny, labored over lines, all the more tentative in pencil, connote the threat of erasure while putting on a brave front. It is equipoise rather than dissonance―”comeheregoaway” rather than “come here/go away” that triggers an immediate, visceral response. I could literally feel my heart melt.

Although Martin’s vision is singular in the nonpareil, it is possible to see a narrative arc (of sorts; more on that later) in the titles of her work. Earlier work is titled in accordance with minimalist trope: untitled, or number five, or such. Then there’s a group of six canvases, tinged with the ethereal colors of Easter eggs and sunrise, which the artist completed in the 1990’s, intended as a single work, called “With my back to the world.” (A documentary by the same name, produced with the artist’s collaboration and released in 2002, is available for those who would like to learn more about the artist. ) It’s a poemy statement (linguistically) in the (formal) realm of the analytical. Both of these observations are at total odds with the palette―a palette you don’t see in post-war art unless paired with jeering insincerity; an insincerity that Martin, perhaps, wanted no part of.

It’s not exactly a sociable posture, but it is unapologetically self-serving. And it’s the polar opposite (or, more accurately, polar inversion) of two of the last canvases: she returns to a dark, somber black and white palette in a dyad named, “Homage to Life” and “The Sea.”

I want to say more about the actual draftsmanship of Agnes Martin. As I’ve stated, and many other critics have stated before me, it’s the intimacy and fragility of her linework that is totally unique. And that oft citied fragility, like everything in Martin’s world, goes beyond duality and reminds me of spider webs, which, for all their gossamer aura, are stronger than steel cables when engineers do a mathematical comparison. There is a Zen quality to the work, too, in that on close examination what a non-artist might think is easy (“draw straight lines” “draw a row of boxes” “draw a grid”) is easy only if it’s done callously, hence, imperfectly. Any one of us can replicate graph paper with a ruler or other straight-edge, but there will be tell-tale signs; in eliminating the callous, we enter the realm of the purportedly tenuous, the imperfectly perfect.

This content is copyright, 2016, Moira Cue, The Hollywood Sentinel, all world rights reserved. Contact Moira Cue at the front page of this sites’ contact box.