A short conversation this year with the amicable Peter Falk of Rediscovered Masters brought to the forefront of my mind a series of questions: How do we as critics and as a society judge—assuming, against the conventional wisdom, that such cases fly under the radar far more frequently than we realize—extraordinary talent that has been more successful in the creation of artistic works of genius than in demanding the world recognize their accomplishment? Whose “responsibility” is it to promote an artist? Is art removed from commercial demands more “pure” than art that “panders” to an audience? As audiences and critics, do we have the right, and do we have the obligation, to look to marginalized communities before we make our lists of greats?

Moreover, are arbitrary or biologically-predicated divisions in gnostic classification of knowledge and field development (i.e. gnostic etiology) responsible for “blind spots” within our culture which are antithetical to, at best, the survival of uncompromising artists (look at the number of “greats” whose lives have ended in suicide), and at worst (eg. the tragedy of Tesla, free energy, and ecocide) the long-term survival of the species?

Are the characteristics required to succeed in the humanities antithetical to those that make us most humane? According to a study publicized by NPR in 2013, if you graduate with a degree in engineering the average starting salary is $120,000. If you graduate with a degree in any of the arts, including the “caring” professions, the average starting salary is about $40,000. With the basic monetary reward system so off-balance, only precious few who aspire to paint or sing (for the sake of two of my articles for this issue of The Hollywood Sentinel) ever achieve the level of success of making their living off of their art or having the financial freedom to pursue these activities in a way that enables them to develop a personal style or contribute to the field as a whole.

Assuming an artist is not born into privilege, she must rely on an exterior source of financial support when getting started; be it the state, such as artists on student loans or in formerly Communist countries; or a personal relationship, which is stereotypically though not necessarily predatory and/or sexual in nature. These often compromised positions produce a form of self-censorship: Soviet artists during the heyday of Communism were expected to follow certain style rules, just as submission and lack of personal criticism would be expected in a young protegé of a music industry executive.

The economic machine driving art and music creates further boundaries to the natural expression of art for art’s sake in differing manners. In the post-Communist, post-modern visual arts world today, the work is supported by few wealthy patrons; the ability to comply with social norms particular to that class or social inclusion into a sub-class of academicians deemed worthy of institutional support is paramount. In commercial music, the art must appeal to the masses; youth, beauty, the ability to make a visual spectacle, a certain persona, all affect what we hear, though in reality music has nothing to do with looks or posturing. In both cases, introversion and the ability to soul-search, moral considerations in the face of demoralizing systemic injustices, and a primary commitment to art can all hinder commercial opportunity for an artist, in the small percentage of cases where the artist’s failure to achieve recognition cannot be blamed on a level of talent, originality, or mastery that simply falls short. (I would furthermore argue that some biases, such as the geographic, are sacrosanct, while others, such as gender bias in painting, are beginning to erode. But while women may exhibit more frequently, as recently as 2009 prominent critic Jerry Salz accused the venerable Museum of Modern Art of “a form of gender-based apartheid.” Only four percent of its permanent collection on display consists of works by women, according to the Rediscovered Masters website.)

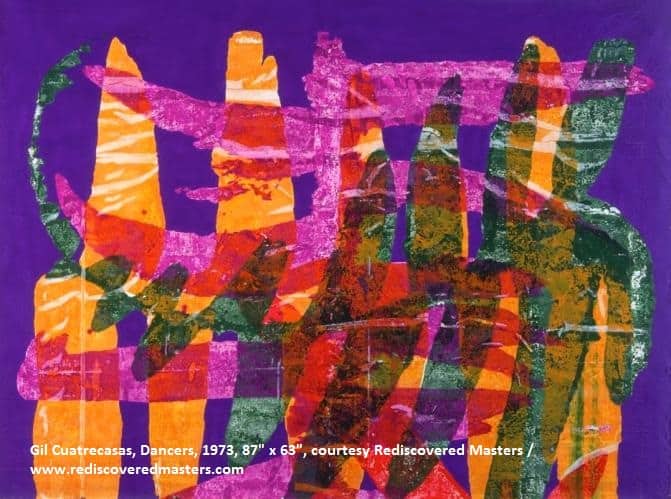

One of the best things about the LA Art Show (for me this year) was Rediscovered Master’s exhibit of the Gil Cuatrecasas Torino Collection (1970-1976). Curator Peter Falk states that “Cuatrecasas was a genius of single-minded pursuit who created his own unique style. Then he suddenly slipped from sight. Now his collection presents a new and compelling chapter in art history, shared by America and Spain.” The gallery’s artist catalog tells the entire story of the Torino Collection discovery, and an excerpt thereof follows:

“Unfortunately, parallel with Cuatrecasa’s early success, he suffered some depressing experiences. First, the promise of marriage to a woman with whom he had fallen in love while at Harvard fell apart. Next, his dealings with art galleries, and the related financial issues left him deeply disenchanted.

…Understanding the wellspring of any artist’s creativity is often a difficult task. And Cuatrecasas compounded this task because he was purposely discreet, refusing to speak about his sources of inspiration or the messages he wished his paintings to impart. His role as a colorist began at Yale with Albers and continued to develop in Mexico and Washington. However, it is clear that the shapes he imbued with color reveal that their fountainhead was his exposure to and fascination with his father’s lifelong obsession with discovering and documenting what came to be 126 species of a rare plant form that only exists at an altitude of about 15,000 feet in the northern end of the Andes mountain range—the Espeletia, commonly known as the Frailejón. This bizarre plant produces daisy-like flowers that are protected by a central cluster of long broad leaves radiating like a crown sitting atop a thick cactus-like column nearly 12 feet tall—the whole appearing as a fantastic surreal sculpture. José’s pioneering work on this rare plant earned him accolades as one of the world’s great botanists. His magnum opus, A Systematic Study of Subtribe Espeletinae, took a lifetime and was so massive that it was published 17 years posthumously in 2013.

It is not surprising, then, that his boys found great pleasure examining various life forms with the microscope given to them by their father. Gil was particularly fascinated by his father’s botanical drawings of the plant’s parts, especially its distinctive broad leaves.”

If you are fortunate enough to have the wherewithal to invest in world-class paintings, a Cuatrecasas canvas is a wise investment. The canvases themselves invite multiple looks, being richly textured through innovative formal techniques employing printing techniques and decalcomania. Cuatrecasas covered his tracks; it is difficult to figure out exactly how the pieces were made. Current prices do not adequately reflect the artist’s stature, which I predict will one day rise on par with his contemporaries such as friend Morris Louis. A Morris Louis may currently sell for three-quarters of a million dollars or higher. A Cuatrecasas can be had for 35-200k. I know that dealers will tell buyers to buy what they love, but I think it is perfectly reasonable to buy art as an investment vehicle in cases like this. The ROI is a good bet.

The mission at Rediscovered Masters is to find artists like Cuatrecasas whose work reflects the highest level of talent and development but who, for reasons of personality or other external barriers to recognition (such as living in a small town; being a female, especially in an earlier era, having enough personal wealth to afford to work in isolation and lack any incentive to sell; etc.) did not “play the game” well. Long before I knew about this gallery, who represent many fascinating artists you may want to discover, I thought that someone should do what they’re doing: go out and look for artists and be willing to question established presuppositions about value. Rediscovered Masters works with gallerists and museum collectors to match an artist or artist’s estate to the best opportunity.

There were many other fine and exciting works at the LA Art Show, far more than I have time to do justice to here, but I will attempt a short list. At PYO Gallery, the carefully delineated drawings of Cha Young Seok have a childlike innocence and whimsy that is as appealing as it is addictive.

Historicana, specializing in Arthur Szyk, an early 20th century Polish-American illustrator, was another fabulous discovery. Szyk’s work directly attacked Fascism and the Nazi regime, so it’s entertaining from a social perspective, but it’s also exciting for the amazing level of detail Szyk brings as a draftsman. His intricately rendered figures are all the more compelling because of their miniature scale.

I always enjoy experiencing new Chinese developments, and enjoyed the selections presented by the China Cultural Media Group, a large state-owned enterprise under the Ministry of Culture of the People’s Republic of China. This year I participated as an audience member in a lecture by Li Gang, whose work explores traditional Chinese cosmologies in a contemporary manner. It was as much fun to hear him talk about his relationship to the work and evolving process as it was to see his work in person. I admire very much his personal discipline and eager, competitive nature. The question I asked during the Q&A session was in regard to the virtue in the speed in which many Chinese works of art are created. The artist answered that the execution may be rapid, but much time and contemplation is part of the preparation. In my opinion, the speed techniques have much in common with dance or martial arts and “not thinking.” When we say “thinking” we mean “mental chatter,” and when we say perceiving, we mean “not thinking.” I think that art and thinking are separate processes. Art is not language. It is pictures. Despite all the claims about thinking in pictures, most of our communication is done with words, and when we create pictures, I hope, we can transcend some of the weaknesses and cultural boundaries of language.

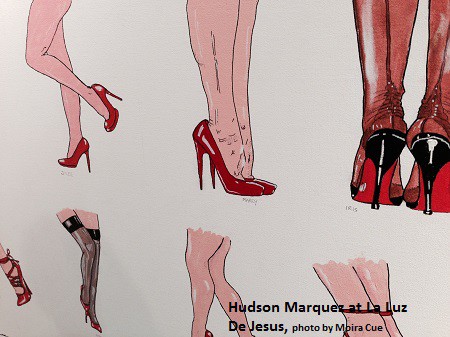

The estate of Bert Stern presented rare last photographs of Marilyn Monroe and other iconic works of limited availability. Bruce Lurie again presented pop art sensation Dan Monteavaro. La Luz De Jesus presented Hudson Marquez (and others). Galleries such as Quidley & Company and Rehs Galleries, Inc. catered to more conservative taste. The digital and installation artist Pascual Sisto exhibited kaleidoscopic images of cars in transit and a gold dust dracena on carpet inspired by the plant’s foliage. Frida Kahlo appeared in an homage by Alexi Torres at Evan Lurie Gallery. Artists John Brophy (Copro Gallery) and Bruce Richards (Jack Rutberg) paid homage to the Venus of Willendorf. The Columns Gallery presented minimalist near monochrome, distinctly Korean palettes from a group of 1970’s artists whose work reflected the color of daily life. And, refreshingly, the United Arab Emirates honored their Bedouin ancestors by feeding us all dates in low white tents set up in an oasis of calm in the middle of all this excitement.

This content is ©2015, The Hollywood Sentinel / Moira Cue, all rights reserved. The Hollywood Sentinel does not necessarily endorse any advertisements or links that may be found on this page or videos herein.