By Moira Cue

I never would have met Seda Saar (the second time) if I hadn’t joined the Los Angeles Art Association. I never would have joined the Los Angeles Art Association if I hadn’t been trying to help a friend, an attorney, find work with an arts-related nonprofit.

I met Peter Mays, executive director of the LAA, at the 2019 LA Art Show VIP Gala. (Peter’s impressive creds include serving as co-chair on the Education Committee for the Board of Directors for the MOCA Contemporaries.)

The lone attorney on their advisory board had just stepped down and they needed occasional help. I wound up on their email list and checked out a couple of events before I decided to join.

What stood out to me at the first LAA event I went to was that the social vibe was totally different. No social climbers or Hollywood shallow types. No one asked me “what do you do?” in a way that immediately read “what can you do for me?” Instead, I met an older gentleman who cradled his “anxiety dog,” and other introverts—people you can count on to be kind. It was truly endearing. So, when I got the call for artists, I thought, what the heck, why not?

I made it to about two LAA art events before the pandemic hit. At one event, the 2019 Open Show, I noticed one woman who caught my eye, Louisa Miller. Tall, lean, angular, with cropped hair, in her seventies, she stood statuesque, hawkishly staring at a painting. She was so immersed in the work; it was as if no one else was in the room. I immediately wanted to talk to her.

Louisa would introduce me to Frederika Roeder, the moderator for the 2020 Pasadena Critique Group. One of the best things about being in LAA is the critique groups where you get to meet with very nice people who are interested in sharing each other’s art. Our group included Louisa, a serious landscape painter; Olyessa Volk and Viktoria Romanova, both Russian immigrants with two totally unique styles; Frederika, a Southern California surfer girl down to her roots; Katherine Murray-Morse, who’d been in banking and had started painting two years prior; and Richard M. Blanchard, who also has a stunning interior finishing portfolio and celebrity clientele list (http://www.atom-zu.com/).

But THIS article is about Seda.

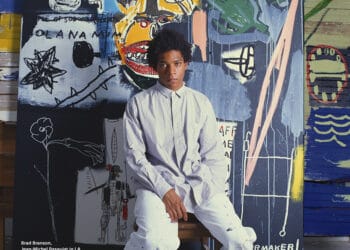

I first met Seda around 2012 or 2013 when she was running the MLY Gallery at the Malibu Lumberyard, which was particularly well known for a star-studded, much talked-about exhibition of a private buyer’s entire Warhol collection.

We met for the second time in Louisa’s spacious, high-ceilinged loft near a trendy Pasadena shopping district for Louisa’s critique (before Covid made in-person meetings unfeasible). Seda carried herself with confidence and authority, declaring certain paintings “successful,” and others “less successful” with an aura of finality. I was lured in by a series of works that amounted to some flirtation that Louisa had made with child-like abstraction. Everyone else was on a different wavelength. During and after the critique, I really connected with Richard and I hoped we’d become good friends.

I didn’t really start to get to know Seda until her one-person show Refractions – a Lens Through Time at the Neutra Museum Gallery (2020). She was gracious enough to make time to give me a personal tour. This was during the autumn wildfires of 2020. My friends in San Francisco and Portland filled their social media feeds with apocalyptic images of a sunless sky, a blood red moon, stories of struggling to breathe in AQI readings that were off the charts. In my own neighborhood, we were under evacuation warning. The entire city of Los Angeles was blanketed in soot and smelled like campfire. The few minutes outdoors between the car and the museum’s front door, even in a KN95, left my eyes stinging, my head pounding, and my throat sore.

The Nuetra is a Silverlake nonprofit, designed by eponymous architect Richard Nuetra, renowned for his influence on Southern California modernist vis-à-vis crisp, steel and glass geometric forms. I can’t imagine a better fit for Saar’s work, which is informed by her study of interior architecture. (Saar holds a BA from London Metropolitan University.) In one area of the exhibition, near a seating area of mid-century Modern sofas and chairs, earlier, smaller, black-and-white renderings on paper of Nuetra-esque architectural forms in nature seamlessly fused Seda’s work with the museum’s purpose.

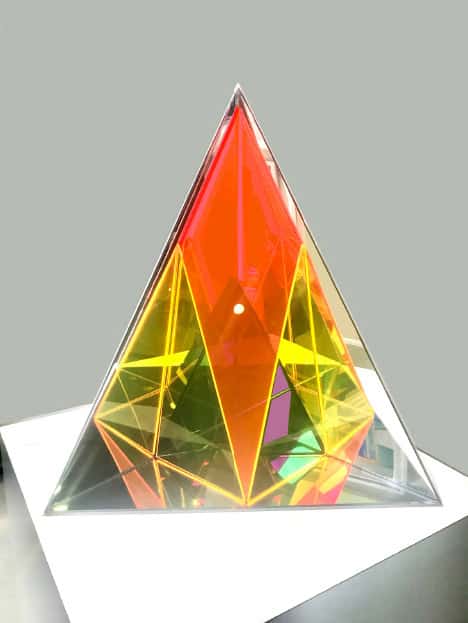

Seda’s work fits into two-dimensional and three-dimensional categories that enhance each other. For example, Saar recently won a Juror’s Award of Excellence for her sculpture, Prismatic, 2019, as part of the California Sculpture SLAM at the San Luis Obispo Museum of Art in 2020. The piece is created with acrylic plastic and mirror in a pyramid shape refracting various jewel-toned colors of light, like a prism.

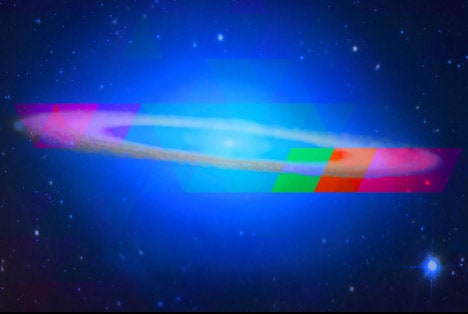

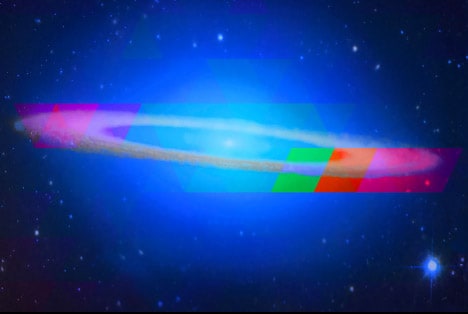

These sculptural works dealing with geometry, color, and light refraction are plastic, three-dimensional versions of paintings and mixed media two-dimensional work that addresses the same formal concerns of space, light, and color. In both cases, one could argue that more is more, and be right; the moreness of three-dimensional objects in space versus the moreness, the meta-ness of a cosmic, or planetary schemata seen in pieces like Genesis.

But what made me excited enough to write about Seda’s work was the added insight that I gained through this private touring.

Here’s where I disclose my biases: I not only write about art, but I make art too. And while I have gone through phases like any artist who has been working several decades, my own work never relies on draftsman’s tools or clean lines. I love work that is childlike, expressionistic, and primitive. Typically, or historically, I’ve found work that was very crisp less interesting. The first exception to this generalization was Agnes Martin; had I not seen the work in person at LACMA, however, its delicacy would have escaped me. The work of Donald Judd’s and Carl Andres of this world still leaves me cold, while the work of the Cy Twomblys and Howard Hodgkins makes my heart sing.

As with Martin and other women working in an oeuvre descended from minimalism or post-minimalism, post-identity, and masculinity, a closer inspection of Saar’s lines and glyphs reveals their fail to establish a machine-like detachment. Her lush, indulgent use of color breaks all the rules of “seriousness” more generally associated with East Coast, rather than West Coast, artists.

And yet I had to get over my own bias of–oh this is geometry, so this is not about nature. And when we talked about the fires, global warming, and cycles of nature, and she insisted that the work was in fact, about nature, my first reaction was dismissive–that she just didn’t know how to talk about her work.

And that’s when the interesting thing happened. As I mentioned, during this discussion the whole city was blanketed in smoke. I’ve lived through fire seasons before, but nothing like 2020. The fires of 2020 taught me how primordial our fear of fire is. Because my reaction was physical and ancient: the one thing we fear as animals is fire, and the one thing that makes us human is that we tamed fire. But the animal fear is deep inside of us, ready to hatch, ready to return us to our instincts: RUN! And a few days later, I would; albeit on an airplane, rather than with my two legs.

When Seda started to talk about chakras, my chakra energy was off, I was in fear mode (well duh, we were worried our house was going to burn down). Honestly, I forget which chakra was the culprit. But she told me that she studied shamanism in Peru, and she decided to walk me through a series of breaths, orations, and gestures intended to rebalance my chakras. I’m not sure I “believe” in chakras, but I’m pretty accommodating, so I went along with it. I don’t know if it changed my chakras or not. I know that something transformed in Seda while she was acting as a shamanic leader. Her voice changed, her presence changed, and we addressed the directions and certain elements of nature. At one point I closed my eyes.

And when it was over, and I opened my eyes, for a second her work came to life. It was no longer just formalism, or what I initially saw as a confused hodgepodge of various movements and thoughts that didn’t “line up” with the finished product. (Why does she keep talking about nature when these are so—quasi hard edge?) She had had a hard time explaining the work. (And why should artists be expected to write their own jingoistic marketing blurbs is beyond me.) But experiencing the work was totally different. I realized that Nature—the nature that I see as wild, as expressionistic, as opposed to geometric forms and straight lines—that Nature at the macro level (galaxies) and micro level (cells) can be very precise, very linear, very geometric.

And so, I had a shamanic experience of opening myself to another vision, another version, of reality. While it required the physical presence of the artist to pull it off, it is, undoubtedly, the highest and rarest achievement in art to break through unseen preconceptions and pull the viewer into the world of the artist.

Moira Cue is an award winning multi-media artist and art critic for The Hollywood Sentinel. She attended the Masters Program of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Learn more about her and contact the author at www.MoiraCue.com

Textual content is © 2021, Hollywood Sentinel. Images provided courtesy of the artist. All world rights reserved.