By Moira Cue

Does your organization practice diversity, professionalism, and inclusion? I would argue that each of these values represents a level of commitment to the same core principal, in ascending order of ethical strength and subtlety. While each value has its place in the contemporary work world, I believe that inclusion is the most important goal to strive for.

Diversity and professionalism can be stepping stairs on the upward path to inclusion, but only if leadership is self-motivated to engage in constant questioning of the status quo. The danger in the “step-by-step” approach is that each step can become a plateau, wherein the organization becomes comfortable at one level and doesn’t go any farther.

An organizational commitment to diversity often focuses on hiring and retention statistics and avoiding legal liability. Adopting policies such as mandatory sexual harassment training for managers, hiring targets for minorities, participation in surveys, and official diversity committees out of fear reduces diverse people, including women, to statistical targets at best; and potential fires to be handled with caution, at worst. It seems true that you can’t improve what you don’t measure. It is also true that quantifiable results, such as the number of African-Americans on your Board of Directors, or the presence or absence of discrimination lawsuits, are the fruits of a particular work culture, leadership attitude, and environment. The root of the problem is deeply held, even subconscious, beliefs of not only the people “in charge,” but the people who come to work for your organization with prior experiences of victimization or discrimination based on their identity. If the main reason you or your leadership engage in a particular course of action is to not get sued, or to decrease future financial loss after a successful suit, than that action is reactive rather than proactive, and your organization should consider moving up the ethics ladder to review and address matters of professionalism from a more holistic vantage point.

On the other hand, there are cases wherein a formal investment in diversity programs signifies progress. Is if your organization refuses to review its own diversity metrics (at least internally); has been the subject of an EEOC disciplinary action or investigation; or has problems retaining women and diverse people at upper levels or with retention in general, then looking at the metrics is a good place to start. If there is no prominent member of your organization who is not white and male and/or from an Ivy League school, certainly you might want to bring in a consultant to ask why that is, and keep an open mind. Don’t assume there is a lack of qualified people applying for jobs with your organization. Upper management or HR may not realize that compared to other organizations of your same size and industry, you have a higher or lower percentage of various ethnicities, so when you analyze the numbers you might see patterns that lead to more important questions. Is diversity not only a product of the organization, but of the industry itself? If so, what factors favor parity in one industry and not another?

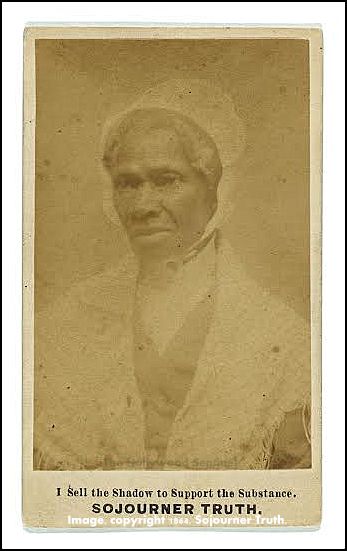

There are entire industries that need to start with diversity: Look at the overall numbers in engineering (http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/wmpd/2013/tables.cfm). Or, closer to home for this author: Look at the numbers of contemporary (i.e. living) female artists exhibiting solo shows in major museums globally compared to the number of women who go through art schools (http://www.artnews.com/2015/05/26/taking-the-measure-of-sexism-facts-figures-and-fixes/). Worse yet, look at a historical list of the highest sales prices for paintings. There are no women artists represented in the top 65 individual sales, and only two men who are not European or American descent (both are Chinese). The most obvious answer to this question could be that one of these industries (engineering) enculturates its own with so called “left-brain,” solutions-based, rational thinking that tends to emphasize the calculating areas of our brains over the care and connectivity centers—so “leveling the playing field” is an alien concept when participants are less aware of the “field” as a sphere of human interaction and more aware of direct, concrete objectives. But art, which traditionally engages the “human story,” is simply a field (much like Hollywood) wherein there is no traditional employer-employee relationship for the makers of individual works of art (or music or entertainment), hence a field wherein threat of litigation plays little to no deterring role for exploitation, and individual personalities battle for “celebrity” status.

A culture that thrives on professionalism (or civility, if you prefer) would exclude cultural appropriation at the expense of the minority. It isn’t professional to boost yourself over others while trampling them under your feet. It isn’t professional to take credit for others accomplishments, pay a person less than she is worth because she lets you get away with it, use racial or sexual slurs, or make someone so uncomfortable that she drops out of your school or company. I’ve had the pleasure of working in organizations led by men, who happened to be white and well compensated, who had this kind of class. Because these leaders saw their subordinates as professionals first, it was easier to do my best work than in other environments where unprofessional and gendered comments were the norm.

But there’s still a higher plane of organizational virtue: inclusion. I often hear the words “diversity and inclusion” brandied about as painter Hedda Sterne famously heard the phrase “great artist,” as if one word. To me this is a pity, as I feel we lose so much of the value of inclusion when we look for diversity reductively or mechanistically. When we strive for diverse work forces, or to give diverse voices cinematic exploration, rather than inclusive work forces or works of art, we only go skin deep. There is an assumption that if a person isn’t a member of a protected class, he or she has never experienced discrimination. There’s an assumption that you can take a snapshot or run your metrics, and know if you are certifiably diverse. There’s an assumption that traditionally excluded people are being “let in” that smacks of paternalism. An inclusive approach throws all assumptions about identity out the window. It’s not management that defines the beingness of their employees by checking off boxes. An inclusive approach is one where real differences, as experienced by the Self, rather than culturally or politically constructed sociology of difference, are given room to be. A progressively inclusive workplace, for example, might create dim, quiet spaces for employees who are disturbed by bright lights or too much noise or accept an introvert’s desire to avoid the company picnic (regardless of disclosure or existence of a formal autism diagnosis). A progressively inclusive workplace would hire art school graduates or creative consultants and ask “how can we be more creative” during Board meetings. You would see not just different skin colors or sexual orientations, but different personalities, different politics, different religions, working together.

My personal working hypothesis regarding inclusion, perhaps due to indoctrination in, first, empiricism, and secondly, a “post-” everything ethos, is that the differences we don’t see—arbitrary epistemological boundaries—are more individualistic and profound than differences attributed to diverse variables. Though there is so much overlap that diverse variables become the simplest way of pre-judging others. By “arbitrary epistemological boundaries” I mean the invisible hierarchy of values which are unique to every field of knowledge as historically defined, without elimination of Western or ‘civilized’ bias. (Two excellent books exploring gender and nature, Carolyn Anne Merchant’s The Death of Nature, and Leonard Shlain’s The Goddess Versus the Alphabet, were key to my early inspiration in this regard as well.) Historical divisions between commercial activity and the academy, art and science, ethics and all other fields of endeavor, have created poly-fragmentated dissociation en masse. We go to work exclusively to make money. We go to school exclusively to learn. We make art exclusively to express ourselves. If we question the impact of any of these activities on non-human life, we have stepped outside of all -ologies other than ecology. Competition and cooperation have prescripted dominant-subordinate relationships in various settings.

Both in your individual success and the success of the organizations you influence, identifying the “invisible walls” more clearly and including ideas, modalities, and people “outside” those boundaries can yield adventure, discovery, and original ideas and combinations.

This story is ©2016, The Hollywood Sentinel, Moira Cue, all world rights reserved.