by Moira Cue

Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus….

– Homer’s Iliad

I’ve been thinking this week about the rationing of cruelty.

We are told it is ok to euthanize pets, but wrong to euthanize our grandmothers. Which do we love more? Is it more cruel to squeeze the last moments of life from a sentient being who is in terrible pain, or to say, “You’ve had enough?”

How many artists hear of 7-figure sales and think, “It should be me,” and what percentage of those ever get there? What percentage of those who do “make it” had class advantages to begin with? Does struggle make an artist stronger, or does it destroy great art before it is made? Is it kinder to pour weed killer all over an artist’s fragile ego, or mete out cruel truths in small rations….(?)

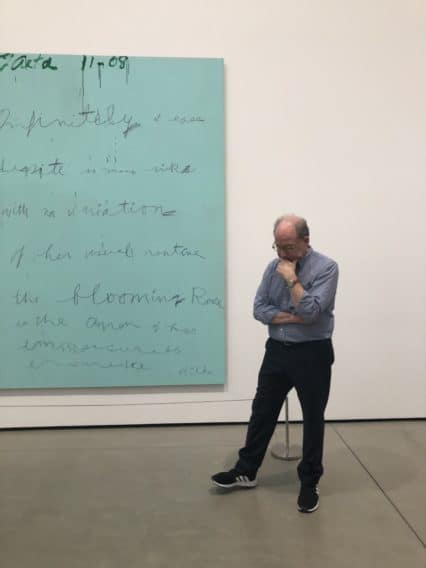

Jerry Saltz, the Pulitzer-Prize winning art critic, was at The Broad today. I was there.

I was so excited to meet Jerry that I woke up several hours too early with too little sleep under my belt. I recently started following him on Instagram—Jerry, who was once a truck driver, makes my heart pitter-patter with the glee that you feel when someone says out-loud things that you are “not supposed” to say. Overproduction. Hype. Idiocy foisted to the moneyed class as avant-garde. Dirty little secrets.

I’m not saying Saltz’s tell-it-like-it-is style makes him the DJT of the art world. (Or does it? Jerry let us know several times this morning that he is a sociopath. My analysis of Trump is that his narcissism is a dangerously benign mask for his core disorder, sociopathy. Resist_Persist_Repeat)

Side note: An Excerpt from Quora Answer to “How do psychopaths and sociopaths think?” (Courtesy Simon Chatzigiannis)

“Make a plan and execute it. If you don’t exploit people, they will exploit you. That is the way that the world works, and I will stand by that. And it stinks, it stinks so bad, but in order to play, you gotta fight fire with fire. You can’t just back down. You gotta play dirty.”

He continues, “There is no such things as morals. People talk all the time about morals. There’s no morals. Nothing’s right, nothing’s wrong. It is all perception, it is all you perceive. Don’t let anybody tell you anything else. Every situation is different. It is not all black and white.”

For the record, I do not endorse a Machiavellian ethos. Nothing is more destructive in the long run than the abandonment of one’s moral code in the pursuit of power.

When I found out, through Instagram, that Jerry would be at The Broad in Los Angeles, instead of applying for a press pass, I paid $150 to get in. I was afraid tickets would sell out. The man is a rock star.

Jerry was across the street when I arrived, either getting coffee or water. I wanted to be sure he could find convenience store coffee, and I don’t recall our exchange except that he said the word “boom.” I was so groggy I couldn’t process language. There are mostly European-style cafes near The Broad, and the best coffee places (Barista Society, For Five, and Nossa Familia) are closed Saturday. But Jerry drinks American coffee, the 7-11 stuff. If you follow him on Instagram, you’ll see the “Big Gulp” featured prominently.

Anyway, after saying hello, Jerry left while the crowd assembled. Then he came back. We all were admitted with wristbands, and waited for stragglers to show up in the lobby (there were a few nice women there I made friends with immediately). And then Jerry began his “overly long introduction” and labeled us all vampires. We were game. Following the Pied Piper. He told us he hated all of us. I don’t care about any of you, just the stuff you make. Somehow he deduced that the crowd would be full of artists. No one disabused him of the notion.

CUT TO: The Lobby, Below the Escalator (Jerry declared this area the museum’s duodenum, due to its unique architectural attributes). Just for the occasion, I was wearing my “love” earring on one ear and my “hate” earring on the other. Jerry pretended to monologue as if he was a painting. “Come here….” The painting plays a game of mystery and seduction.

According to Jerry, cities vote Democratic because love is the glue that keeps our innate hostility from taking over. Whereas, in flyover country, people are so far apart they don’t have to use love as a connective tissue. The hostility hardens to hate, and they vote Republican. (His words, not mine, but I’ve bastardized them completely.)

Next week, he tells us, he will publish a numbered list of rules in New York Magazine. He will return to this topic to let us know the list includes “Though shalt not envy…” At the top of the escalator we are greeted by a big shiny Koons. I thought the subject was balloons, but they’re called tulips. They looked exactly like tulips made out of those long skinny balloons though, not real tulips, but oversized balloon tulips cast in a reflective stainless steel.

I think of Koons as a big balloon. And I think how these are the works that attract people who only go to museums to take selfies in front of the art. And I can’t get past the wall that says “means of production is mine,” and I don’t like bright shiny objects. I like dirty, broken objects. Stains on sidewalks. Displays of dexterity. Things with layers. But we say nice things in The Hollywood Sentinel, that’s our schtick. So kudos to Koons for positioning and marketing himself so well. It’s not an easy accomplishment.

To consider Koons in the best light, I should ponder the artist’s generosity and glee. (When my cat brings the severed head of a mouse, I know she means well.) Knowing that Koons experiences pleasure from things that repel me (plastic toys, artificial things, etc.) I can consider that perhaps in the giving of what is beloved, his intentions are kind. I had never thought of that before. This is Jerry’s influence. He also writes that what we hate in another artist’s work is often something inside of us. Which gives pause to consideration.

Jerry addressed us as devotees, as children, and, worst of all, as *aspiring artists.* And by worst of all, I mean, it felt like one of those Hollywood parties that doubles as an open call. Where you know someone who was invited by a friend of a friend will embarrass himself and try to give the host a headshot.

So, we started with Koons, and then we discussed Mehretu, Bradford, and market corrections regarding women and people of color in the art world. I think he overstated the good news for women and POC’s. (Out of the 100 most expensive paintings ever sold at auction, not a single female artist is represented.) He talked about market corrections, and we didn’t get into the role of historical excavation. But based on his statements on Hilma Af Klint, I know he’s thought about the issue.

Next we visited a Warhol room.

“What do you see? I want you to see the subject and not see the subject.”

“What is the subject?” “How is this created?”

He talked about Warhol as a train that rattled the tracks. Warhol shook everything.

In the next room he talked about Johns, who dreamt he painted the American flag, and woke up, and painted the flag. When asked about the materials, an audience member pointed out that encaustic won’t bleed colors. I said encaustic also served as an adhesive to hold the newspaper to the canvas. Jerry went after Mehretu (again). He said her thoughts about diaspora weren’t embedded in the work. Ouch.

And this is a whole other topic, where social issues are used to justify an artist making whatever type of work she wants. Does the text used to market the work actually relate to the work? (Or, in the words of the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy CEU I was listening to at 3:00 am recently, is language the cause of suffering? Why do we rely on words to validate pictures?)

I digress.

Recently, I saw the work of an artist of Middle Eastern descent. These were luxurious semi-Westernized nude figures in the Persian miniature tradition, but large scale, on fine linen. The accompanying booklet of text contained a didactic lecture about the refugee crisis. Of course we all care about refugees, but the artist insisted on a non-existent relationship. All I could do was inwardly roll my eyes, and leave. [End rant.]

Jerry mentioned that he could take Mehretu’s work, put it in another gallery, and tell us it was a third-string AbEx artist from the fifties. I.e. She was “thinking about the diaspora” my -ss.

We moved on to Ellsworth Kelly (shape and color; eliminate the artist’s hand) and he asked me to stop answering questions and give someone else a turn. This, of course, was embarrassing. Luckily I wear big girl panties now. So no biggie.

Channeling Doris Lessing, The Golden Notebook:

Somewhere around the third or fourth time Jerry used the word sociopath, after Ellsworth Kelly, I began to wonder if I was a sociopath, or a conditional sociopath, a compartmentalized sociopath. Is it fun to be a sociopath? How can I be a sociopath if I’m also an empath? Is the empathy I display “displayed empathy”? What if there’s another layer of me that has no empathy? Is art a no-empathy zone in my life? Is empathy a form of cruelty? I started to feel like I was wearing myself in layers. This hysterical panic lasted a full forty-five seconds.

Then, Ed Ruscha. We looked at Norms on Fire. We talked about LA cool. We talked about working outdoors, being outdoors, Pop art and the everyday. Then we moved on to Anselm Kiefer.

We completely ignored Beuys(!)

Our path also avoided many Lichtenstein’s, and Barbara Kruger. And that giant table and chairs that people always take pictures of themselves under.

The Kiefer was not a particularly good one (compared to the rest of his oeuvre). It was done in charcoal and light washes (Jerry thinks he did rubbings, but I respectfully posit the grainlines in the wood are created via draftsmanship; the perspective gives it away). This painting, Deutschlands Geisteshelden (Germany’s spiritual heroes) visits the theme of post-war German identity. I think Nürnberg, also in the Broad collection, but not currently on display, is a better painting. Kiefer is best doing what he is known for—tactile surfaces, layers of paint three inches deep. But Jerry wanted to talk about what if your parents were Nazis. Can good people love bad people?

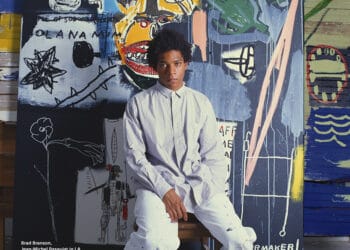

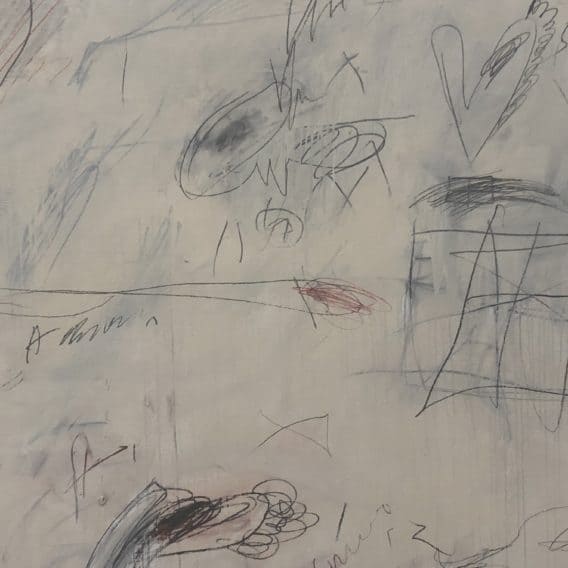

By the time we got to Kiefer, the museum had opened, and a troop of Brownies wandered through. “How do we get out?” Jerry asked. “Through Twombly!” I replied. Of course. I’d forgotten to shut up. He said he wasn’t going to talk about Twombly. We were probably 45 minutes over our allotted time by that point. But he couldn’t help himself. He asked us about Twombly’s pencil scrawls of genitals or hearts; love or war, and he talked about how real Twombly’s vulnerability was. Radical vulnerability. He announced we’d wrap up with selfies for everyone, and I blurted out that we’d missed Basquiat.

Jean-Paul, I’m sorry. It was not to be.

Last stop, Kara Walker. Jerry made white girls in nice clothes say dirty words. “What is going on here? I want you to SAY IT OUTLOUD.” Kara, like Mehretu, was his student at RISD. Even then, she was doing cutouts. When Jerry first saw her, he looked over her shoulder chills went up and down his spine and electricity through his head and he said to himself, “I’m not going to say anything to this artist and f— it up.” Speaking of f bombs, he also said we should all have a sign over our studio door. The sign over his typewriter says, “I’m not going to f— it up again this time.” (Something like that.)

And then, the lecture concluded and we were given an opportunity to ask questions. One young lady (in a leopard print jumpsuit) for some reason, maybe the Beatles effect, looked like she was about to cry. She asked about the gallery system, mega-galleries, etc. Another woman asked about pricing, and mentioned her work had been at Basel, but didn’t sell. Tough break. Jerry started talking about Koons again. In the early days, Koons price gouged himself and sold work at a loss. He sacrificed his children. “Anything you do, any price you pay, for your art is ok!”

In front of Lari Pittman, we took selfies.

I waited to be last, and then I hated the way the picture turned out, and hated myself for posing for a photo with Jerry like a groupie. Jerry said “You did good,” which translates to “you talk a lot,” and then he said “You’re a real artist,” and I said, “whatever.” Then I all but ran out of the museum with my hair on fire, as shocked at the word “whatever” coming out of my mouth as I was when my eighty-plus year old father used it.

Outside, I had a cup of tea. I sat near the grass, after trying to talk to another troupe of Brownies who were offended because they were actually Girl Scouts and I didn’t know the difference. I thought Brownies wore brown and Girl Scouts wore green. But these Girl Scouts wore brown and didn’t look any older than the Brownies. So I stuck to singing “Leaving on a Jet Plane” along with a sidewalk musician:

So kiss me and smile for me

Tell me that you’ll wait for me

Hold me like you’ll never let me go …

… then went back to pay my respect to Basquiat. And I thought about the question I’d asked, back at Walker, about the arc of a painter’s career. And my follow up question, what about the roses? Who gets better with time? Hodgkin, who else? Most all of them get worse, or plateau, at best. What about Twombly’s roses? I’m not sold, but I can’t write them off. They’re stuck in my craw.

The Twombly room has the iconic neutral palette work, sculptures that no one looks at, and one of the late roses, with an inscription. I had asked Jerry what he thought about the roses, and Jerry asked me what I thought, before saying “color is good” and they’re “a little dry.” At least I think it was a little dry, or, something to that effect.

I’ve read the glowing reviews but I’m not fully sold. Did Twombly go Pop at the end? Is that it?

I went back again, to this painting, to look for Twombly in Twombly and I see he’s already left us. Someone else is there instead. Is this really a burst of bloom or an obtuse inaccessibility—the moment of being so present that one is gone, the point in the Monad where fullness and nothingness, yin and yang, emerge from each other? Do we assign false significance to late work, or do we attack it because we no longer understand it? Roses are loaded. Are these too grandiose a farewell, or betting the House one last time and failing? Again, I return to the idea that he’s suddenly integrated the Pop movement into his signature style. The Twombly roses remind me of Warhol’s flowers.

Rose V, at The Broad, contains the following inscription of a section of a poem by Rilke:

Infinitely at ease

despite so many risks,

with no variation

of her usual routine,

the blooming rose is the omen

of her immeasurable endurance.

I watched a pretty little girl, no more than eight, pose in front of the painting. Once she knew it was a painting of roses, she liked it. And I remembered suddenly I’d also made an appointment to see a video installation by Jordan Wolfson, called “Female Figure.” I signed up on a whim, because I tried to walk in and couldn’t, and the attendant told me to come back in 15 minutes when there was a spot open due to cancellation.

I enter this room and the first thing I see is a stripper, who turns out to be a robot. You might be confused if you were only looking at her rear end. She’s very life-like. And the voice in the sound installation says, “My mother’s dead, my father’s dead, I’m gay, I’d like to be a poet. This is my house.” Our stripper wears a green mask with the visage of an evil witch, and she twerks to dance music, and makes eye contact, and tells you what to do.

You kind of had to be there.

This content is ©2018, Moira Cue, Hollywood Sentinel, all world rights reserved.