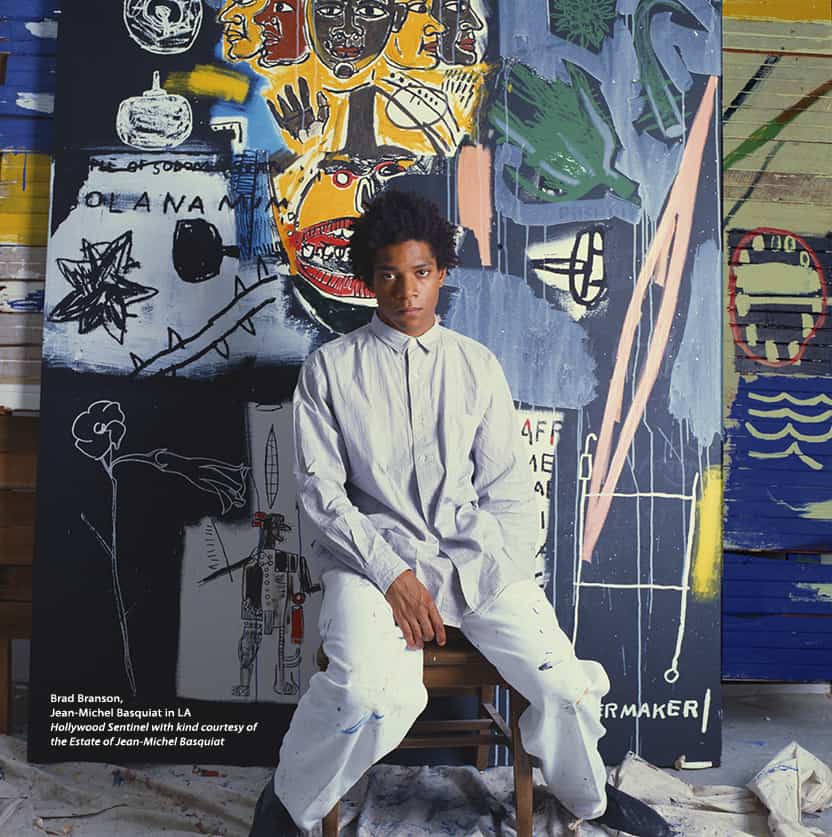

A unique exhibit, “Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure©,” opened March 31, 2023, at The Grand LA, a dynamic city center designed by Frank Gehry that includes luxury hotel rooms, full-time residences, and access to fine dining and entertainment amenities. Unlike retrospectives for major artists held in white-walled, brightly-lit museums, this show blends high art with a more intimate, funky-yet-accessible approach to the artist’s life and work. The show runs through July 31, so there is plenty of time to go see it, more than once if you like. With more than 200 never or rarely seen works by the iconic 1980’s neo-expressionist New York painter, there’s more than 200 reasons to go back for seconds.

We arrived on a Saturday when lines for admission stretched out onto a nearby sidewalk. The exhibition was organized into four separate galleries on the ground floor of the sleek complex. The first gallery, also the largest, included personal memorabilia such as Basquiat’s father’s address book and the announcement of his birth. Works on paper, including child-like drawings inspired, we’re told, by Saturday morning cartoons, were framed on narrow paneled walls.

King Pleasure© takes its title from a painting created by Jean-Michel in 1987, as well as the name of a bebop loving bartender turned jazz vocalist whose “Moody’s Mood For Love” closed out Frankie Crocker’s show on WBLS, and marked a place in time for the Basquiat family. – Shannon Cosgrove

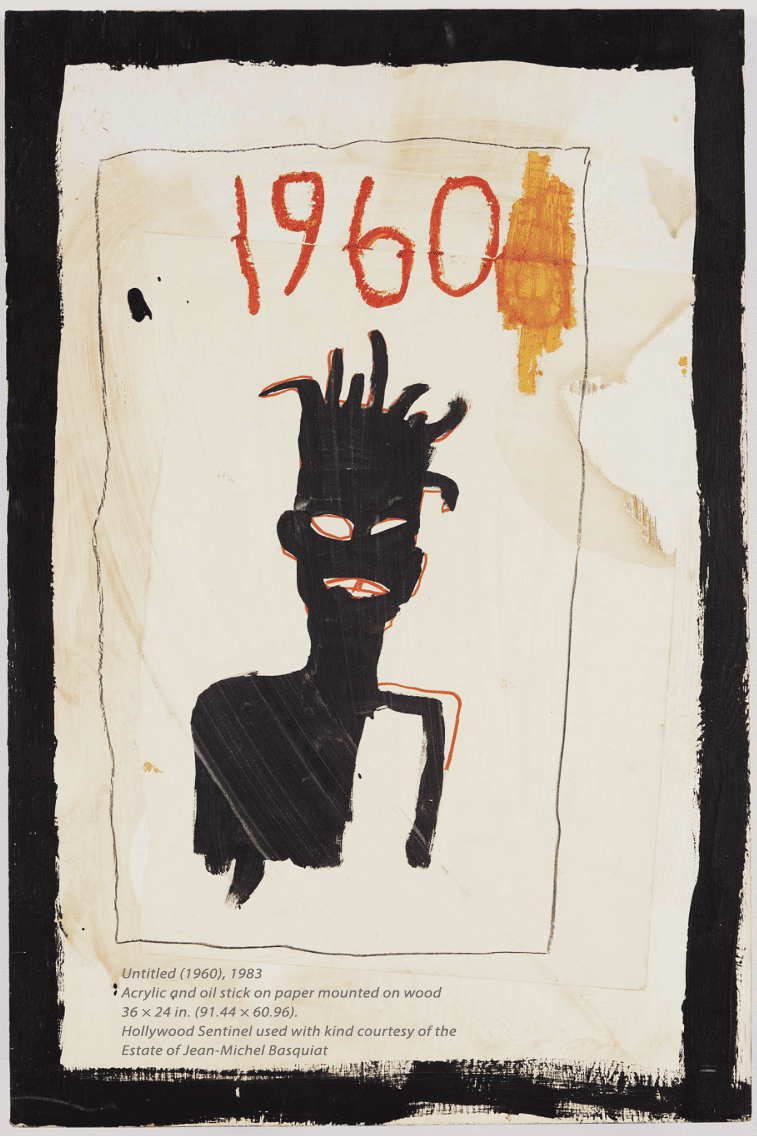

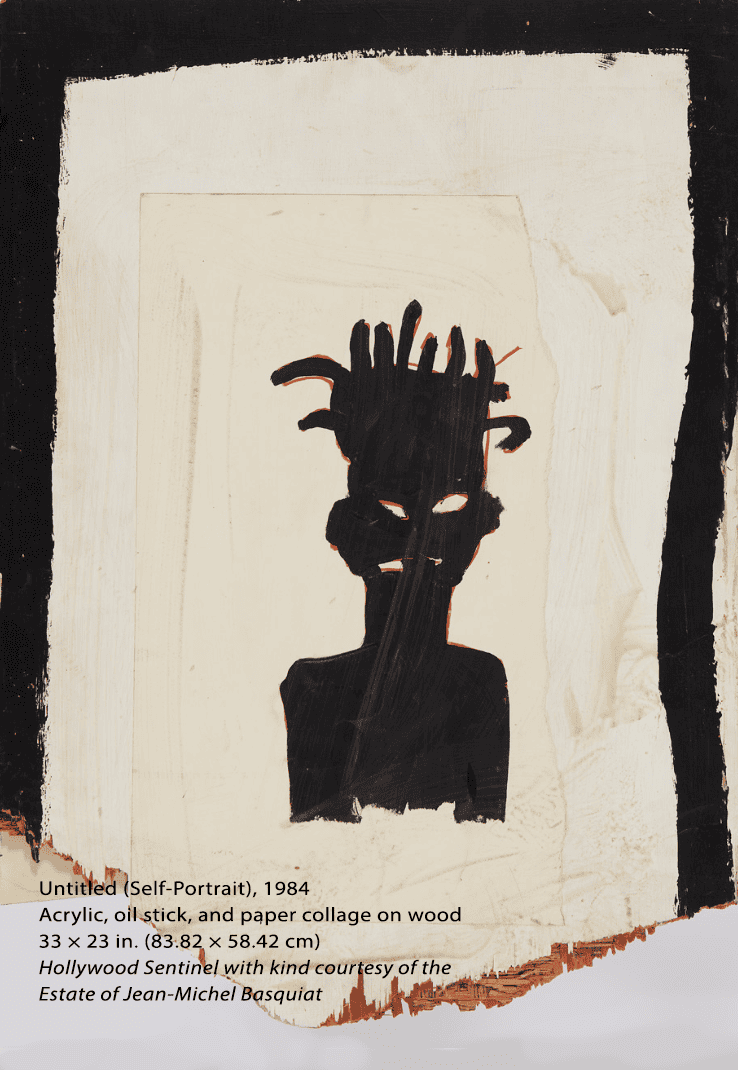

The first “gallery” in the exhibit includes several maze-like hallways paneled with a very 1980’s wood veneer and two recreations of rooms in the family’s early home, reminiscent of period or specimen dioramas in a history or natural history museum. The first hall in that gallery includes two silhouetted minimal quasi self-portraits, titled Untitled (1960), made in 1983, and Untitled (Self-Portrait), from 1984.

Basquiat’s commercial success began somewhere between 1981 and 1982. These two pieces have both the gritty, raw energy of his early graffiti art under the name SAMO, and a newfound sense of self-assurance that typically comes with being known as an art star. Basquiat used what looked to me like black oil stick, red crayon, and a white acrylic undercoat at first glance and perhaps red marker or red oil stick and black acrylic on second glance (the cards say “oil stick and acrylic on paper mounted on wood”) outline and fill in a Black man with funky, floppy dreads who is identifiable by his shape and the rawness of the line (revealing a blend of influences from Debuffet’s Art Brut to tribal or African diaspora artifacts). The facial features of the figure, who appears in both works, are insinuated through negative space: blank white for eyes and lips, the blank space outlines in red line that obeys its own laws of linear form-making rather than the shape-making of blocks of color.

Line and color are distinct, separate entities in most if not all of Basquiat’s work. This gives it all a feeling of Jazz. But back to these two self-portraits. They spoke to me with a prescient sadness of his untimely death in 1988 at the age of 27 due to an accidental heroin overdose. There is something funerary, elegiac in the Japanese Edo sense of the word, boxed and precious, but also tragic, as they stare directly at the viewer but refuse to show us what’s behind the blank of their eyes. Above one figure the words “1960” are scrawled with an extra zero at the end that turned into a smiley face that was then scrubbed out with an over-wash of ochre yellow. In this same picture the paper appears yellowed and torn, there is a box drawn around the edge with a fragile pencil quality, and then another box in thick matte black around the entire canvas space. There’s a random spattle of off-white in the upper right-hand corner and a few loose drops of black even feels/moves like Japanese ink (or watered-down acrylic) in the upper left. Some type of ridge or indentation around the eyes looks like eye masks you’d wear at a Carnival masquerade or Mardi Gras, but you must look closely to see it. The entire piece seems to have been done in one sitting.

The other painting with a nearly identical figure, Untitled (Self-Portrait), is done on a jagged piece of what looks like plywood that’s been eaten by a shark and reminds me that Jean-Michel purportedly referred to power players in the art world as such (“a good shark,” he added, in reference to a dealer, according to an interview with a former friend in the British press).

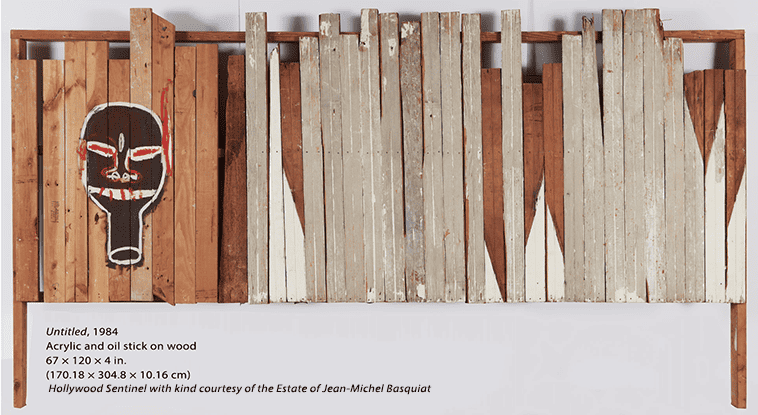

Some of my favorite works by Basquiat are not on canvas but on pieces of found detritus or remind me of repurposed freight palettes, stolen or off-kilter picket fences, or bedding left behind in a warehouse by a squatter before it was demolished to make way for luxury lofts.

One of my favorites, which is Untitled, like many of his works, feels simultaneously neo-Primitive and post-Colonial. I love the beiges and raw wood, the minimalism, the print and pattern, and the sculptural simplicity and sophisticated synchronicity of this work. When people say that he had ingested and digested Picasso and Rauschenberg, this is what they’re talking about.

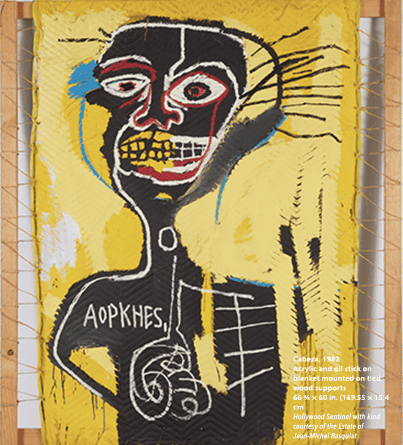

In Cabeza, 1984, a bedsheet is woven onto a wooden frame and the colors are bright and tropical. These and other pieces’ choice of broken, found, and irregular materials (including a very narrow standing door) as a surface, rather than canvas, also call to mind the work of Black Outsider or folk artists whose work he collected, such as Sam Doyle-who painted images of his South Carolinian St. Helena Gullah community on sheet metal and wood-and Alison Saar, who painted Black figures and athletes on metal and mat board. Their work is delightful. And far from the juggernaut prices that Basquiat’s paintings have ascended to in recent years, reaching not just tens but a hundred plus million for one canvas. Because despite his lack of formal education, Basquiat was no outsider. He partied with Warhol and Grace Jones. He dated Madonna. He collaborated with Warhol. He didn’t just look like a fashion model or date fashion models. He was a model. In 1987, at the behest of legendary founder of COMME des GARÇONS, Rei Kawakubo, Basquiat turned heads as he walked the runway for her show.

Moving on to the more intimately scaled Gallery two, the exhibit boasts a recreation of Basquiat’s studio, complete with what looked like an analog television playing VHS tapes. When I walked through The Breakfast Club was on video while 80’s club music played on stereo. A COMME des GARÇONS jacket was on the paint-splattered floor, along with dozens of books on myriad, discursive subjects. It’s fun to see the studio as close to how it was when he was alive and working as they could recreate.

With Basquiat’s frequent use of text in his work, it’s like he’s having a long late-night woozy conversation with all of us in perpetuity. He comments on police brutality, sexual objectification, Black history, art history, commercialism, indigenous people, signs and symbols, and class and capital. His most frequent symbol, the three triangle “crown” icon, is both aspirational and a self-fulfilling prophecy. He would himself go from rising art star to something otherworldly, a tragic icon.

Which is why this show is different. It’s not put on to push an agenda or cement a legacy so much as a labor of love by those who knew a different, more human side of him. His sister Jeanine says, “I never discussed celebrity with Jean-Michel-it wasn’t something that ever really came up in conversation. He always showed up as just my brother. For me, he was the older brother that I laughed and hung out with, so I see him through a completely different lens. It’s both surreal and humbling to hear his fans speak of him in a manner that is so different from my perspective. But I am incredibly proud to hear others talk about how he has inspired them.” His sister Lisane adds, “Jean-Michel’s success was a double-edged sword. He felt quite a bit of pressure. He was so ahead of his time, and he was also very young. There was money involved, and so much recognition-things many people aspire to. He had surpassed many of the folks that he started the journey with, in terms of his success. They were still friends, but his life and what he was dealing with was different from their reality. In spite of that success, though, he was still seen as ‘the other’ by the art world establishment; he didn’t fit in anywhere, really. Being put into a position of having to constantly correct how people saw him deeply annoyed Jean-Michel. He wanted to be seen as an artist, first and foremost, and to have that conversation. It frustrated him to defend himself against people’s prejudices, stereotypes, and assumptions.”

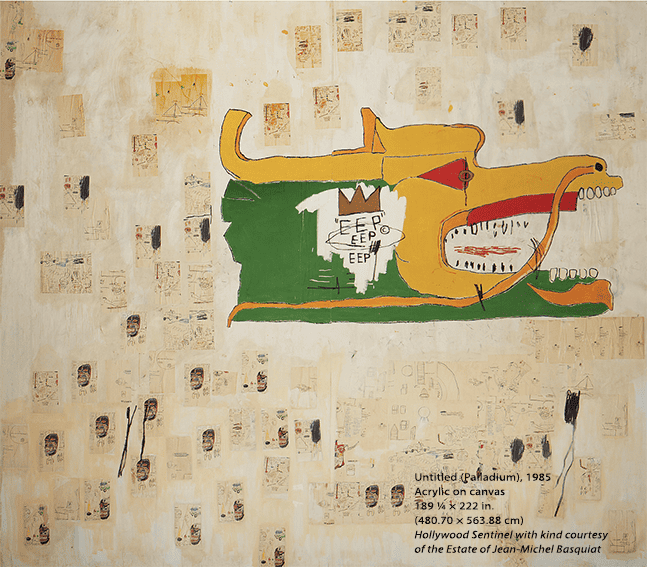

The fourth gallery features very large scale works in a recreated club environment, video installations of his family discussing his legacy and of the 1980’s pre-AIDs club scene, and two monumentally scaled later works that dwarf the viewer. Untitled (Palladium) intrigues me because it features the head of a Chinese dragon, his crown insignia, and measures more than 18 feet in length and almost 16 feet tall. The work was completed in 1985 and shows an artist in full command of his powers. Yet, especially after this show, it’s hard not to imagine what Basquiat could have created had he been fortunate enough to survive his addiction and mature both as a person and artist. So much at such a young age would be hard for any of us, much less someone who was the child of immigrant parents (a strict Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother who was hospitalized for mental illness when he was just eleven years old).

When you hear his step-mother talk about how hard his passing was because “you never expect to lose a child,” and see the pride and awe in the faces of his sisters’ children, when you learn that Basquiat’s father refused to sell any of his work while he was still alive, and when you reflect on the show as a whole, with its lack of pretentiousness and generous attention to detail, you realize that he wasn’t just a great artist. He was somebody’s child, somebody’s brother, and somebody’s uncle. And that might mean even more, in the end.

https://kingpleasure.basquiat.com/

Moira Cue is an independent curator and multi-media artist based in Los Angeles, and Art and Literature Editor for Hollywood Sentinel.

Hollywood Sentinel reports “Only the Good News,” each month, with weekly, and at times daily breaking news in all areas of the arts including music, film, fine art, literature, and more. Visit often, and let us know your comments or questions, and what you want to hear and see by contacting us at 310-226-7176.